Occasionally when I am going through an extra bout of anxiety, I catch myself giving in to self-pity.

Other people don’t have to deal with this kind of crap, I think. If I could shed this self-doubt and fear I’d be so much stronger. Other people have it so much easier. They didn’t go through what I did as a kid.

And then I catch myself, and I think, really?

Don’t get me wrong: I think it’s super-important not to downplay our grief. Unless we sit in our sorrow and anger and bitterness and look at it, examine it, we can’t find healing. But our grief is never an invitation to stay in self-pity long-term.

Oddly enough, the more I’ve faced grief, the more I’ve reckoned with my own story, the less self-pity I feel.

Before I was able to reckon with my own suffering, I held it close to my chest like a shield. I thought, My childhood was so weird, no one else can really understand me. I thought, I can’t expect myself to be anything other than afraid, trapped, full of self-loathing.

See: that’s a lie. It’s a lie that we have to stay trapped. It’s a lie that our suffering has the final say. It’s a lie that our sins or brokenness is the most important and interesting part of us. It’s a lie that our sickness gets us a free pass to not seek healing.

I think we often talk about the sins of the powerful: the proud, the angry, the oppressive, the abusers. We think sin is over there with the people in power. And oh, I think we need to look at that very hard.

But so often, I think we conveniently overlook our own power. Seeing ourself as helpless and pitiable can hamstring us—or worse, hurt other people.

Look: if we’re parents, we have power. If we have jobs and responsibilities, we have power. If we’re white, middle class, able-bodied, we have power.

You know, most people have deep grief, suffering, mental illness, family drama to deal with. And even more people have poverty, structural oppression, micro-aggressions, physical disabilities and other, deeper hurts on top of it. And then, globally, there are political systems in chaos, wars, violence—

Suffering is cheap, my friends. It is an old, old story that we are sore afraid.

But it’s not even about comparing my hurt to others’. The real challenge is this: is our hurt really our entire identity?

What I wish I had known when I was first reckoning with my story was that my hurt was not the most interesting thing about me. That as important as it is to face our limitations, our heartache, that is only a first step out of the darkness. If we stop there, we miss emerging into light.

Reading Between the World and Me, I was struck by Ta-Nehisi Coates’ lack of self-pity. By his realization that the oppression he and his son face—murderous oppression that targets his son’s precious, breathing body—is, to some extent, old news.

Structural racism is something he should not, in any just world, come to terms with. And yet he has no choice. So does he give into despair? Does he allow the systematic oppression he faces to define who he is?

No: he faces the darkness that surrounds his beautiful body and looks hard at it. Questions it, measures it, tests it. Decides to practice freedom and dignity in his own heart, even if the world will deny his right to freedom and dignity. Decides to become more aware, more alive. He doesn’t wish away the ache of injustice and the righteous anger he feels. But he does not stop there.

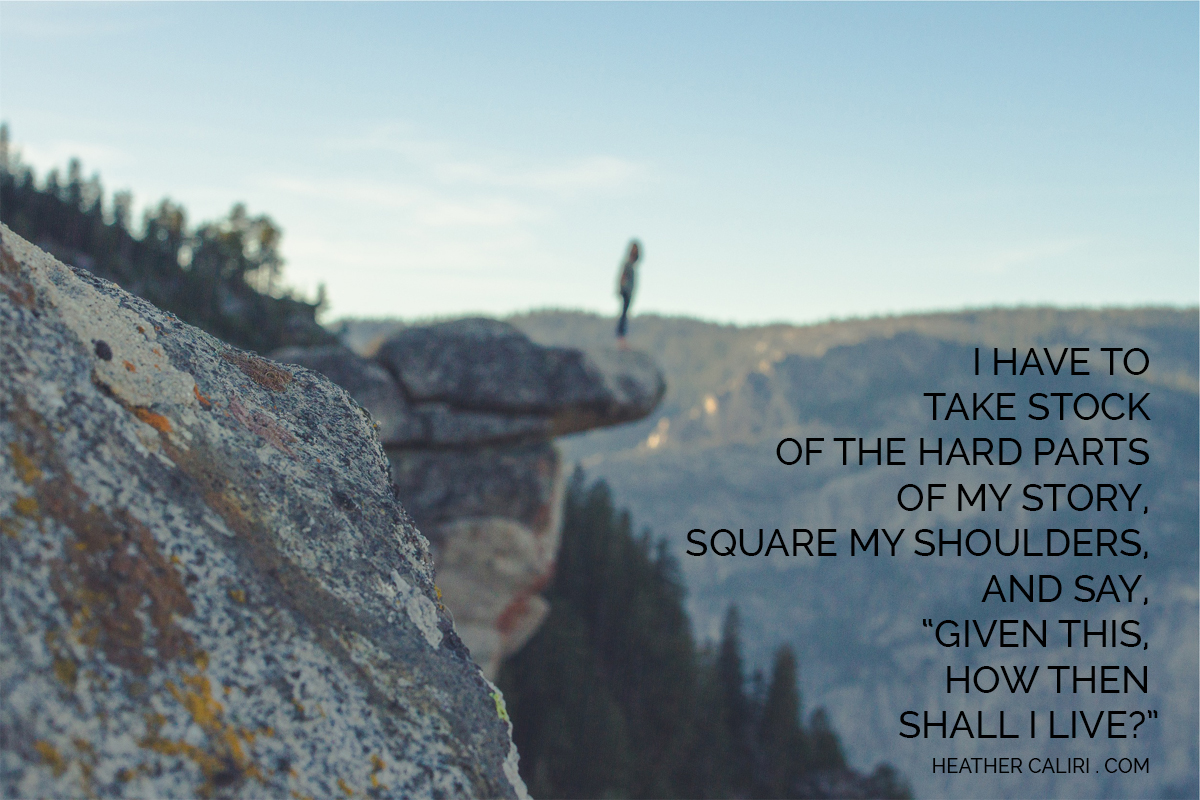

How can I read his much harder story and pity myself? Given his bravery, how can I do any less than take stock of the hard parts of my own story, square my shoulders, and say, Well, okay. Given this, how then shall I live?

Sometimes, I want to use my suffering as an excuse. As an excuse not to take risks, to engage, to love well. As a way to set myself apart, shirk responsibility. To avoid good work or evade showing up.

No more of that.

The older I get, the more I realize that long-term, there is no excuse for living with our heads bowed down in shame and despair. Self-pity is never a way forward.

I get the need to wallow sometimes. Frankly, it’s helpful to have a pity party when we’re first facing our grief. It’s about all we can handle when we come to terms with our sorrow. (a big caveat I can’t speak about those who face structural oppression that I can’t really imagine. Honestly, those who handle those deep burdens teach me how to face suffering with dignity, not the other way around.)

But I suspect no matter our skin color or people group, self-pity isn’t a stopping place. It’s simply not a place to set up camp. No: we have to pick up our crosses, measure their weight, and keep on walking.

Go here to see the whole series of posts on “Beliefs I wish weren’t true”.

Beliefs I Wish Weren’t True: Sins of our Fathers, Part 2

Beliefs I Wish Weren’t True: Sins of our Fathers, Part 2

This is hard but so true. I meant to comment the other day on your newsletter about the whole singing thing. I swear, we must be soul sisters. I’m a singer, too…although I hesitate to call myself one since I haven’t been able to sing publicly for several years due to anxiety.

Anyway, I love this post. I grew up in a home where depression and self-pity were the status quo. When I started learning to lift my head, it was seen as a kind of betrayal by some family members. So it’s a constant struggle…not to fall down and wallow in that pit. Glad to know I’m not the only one who struggles with it!

So bold to write about this, friend! This part: “It’s a lie that our sins or brokenness is the most important and interesting part of us.” This is such a good thing to remember, especially in an era of “selling our story” and “personal branding” and being internet people.

I think there are stages of grief we have to go through when we realize what we’ve been through isn’t right or normal. One of those stages is that “wait, you mean other people don’t go through this?” But we have to move from that stage into empathy for others, accepting that suffering is a reality of our common past while working toward a better future. It’s so easy to get stuck in that pity place of being different. Validation is so good and such a relief. But it isn’t the end game.

Yes, absolutely–there’s this tension between realizing our particular experience may not be as “normal” (if ever there’s a useless word, I think it might be “normal” 🙂 but that also, we’re less alone, less weird than we think–our suffering isn’t isolated, and the forces that oppress us affect others too.

This: “Sometimes, I want to use my suffering as an excuse.” and this: “self-pity isn’t a stopping place. It’s simply not a place to set up camp.” challenged me today. Thank you.

“Given this, how shall I live?” – words to live by, but a challenge to balance sometimes.

Thanks, Kathy. In all of this, we need such relentless kindness towards ourselves and other people. We’ll get nowhere with shame and self-loathing.

Thank you for this series.