First, let’s get this verse out of the way. Quickly.

“The Lord is slow to anger and abounding in steadfast love, forgiving iniquity and transgression, but he will by no means clear the guilty, visiting the iniquity of the fathers on the children, to the third and the fourth generation.” Numbers 14:18, ESV

This verse horrifies me.

As a description of God’s character, it does not leave me eager to make His acquaintance. Perhaps this God abounds in steadfast love, but good luck if your parents are nincompoops.

So I get why it might make you run screaming from the Bible.

However.

The author of Numbers says that God is the subject of this sentence, the one actively visiting punishment on generation after generation. Bible literalists, forgive me, but I have doubts about that.

This was in an era where people thought physical disease was a sign of sin. People assumed misery was God’s judgment. Exhibit A? Job’s friends.

So did the ancient Israelites always have a perfect read on God’s character and how he ades wickedness? Do I?

No.

But regardless of whether you think God’s the subject of this sentence or not, the truth of this verse is incredible. If we write this verse in passive voice to focus less on the actor and more what it’s saying, we get this:

The iniquities of the fathers are visited on the children to the third or fourth generation.

This strikes me as one of the most realistic, helpful statements about sin in the entire Bible.

Here’s what the verse tells me about sin and what I should do to repent of it.

Many things that lead to sin have a genetic component.

Substance abuse runs in families. So do mental disorders.

I’m not (really not) saying having a genetic predisposition to depression is sinful. But the battle against your predisposition to anxiety, schizophrenia or bipolar disorder will provide plenty of opportunities to let sin flourish, just as someone with cancer might give into despair, self-pity, or anger.

(I’m also not saying that the author of Numbers understood genetics. But ‘chip off the old block’ is a traditional understanding of this, no? People have long noticed that parents pass their predispositions to their kids.)

If there are patterns of mental illness in your family, Jesus calls you to take them seriously. It’s not fair that some of us have to manage difficult brain chemistry, but life isn’t fair. We must seek treatment faithfully.

Also, if we’re parents, we should pay attention to how our own struggles with mental health pop up in our kids. If we have learned tools, strategies or healthy ways of coping with less-than-ideal genetics, we need to be intentional about passing them on.

Sin is a communicable social disease.

Besides having roots in genetics, sin is learned, and usually in very insidious, subtle ways. If our parents are narcissists, we get narcissism modeled for us. If they are cruel or passive aggressive, ditto. If we live in a neighborhood filled with violence, as Ta-Nehisi Coates did, we learn aggression as a coping mechanism. If we grow up in a system of white supremacy, we’ll have racism embedded in our worldview.

This is just hard reality.

It might sound odd, but this view of sin actually helps me be more compassionate with people who hurt me (and kind to myself). I can trace the roots of the sins that breed poor choices, unkindness, and foolishness. When I look at people who sin against me, it helps me to remember that if all they can imagine is brokenness, it can be hard to choose otherwise.

It’s not an excuse for sin. But it is a reason for it.

Sin is often systemic, not simply individual.

In our Western, modernist, individualistic framework, we tend to think of our sins as contaminants that go no further than us. Our problem, our responsibility. Someone else’s sins are their responsibility, full stop.

Look, we’re all personally responsible for our own actions. I’m not trying to say otherwise. I have no idea what percentage of our sins are a “sin nature”, how many we invent on our own, and how many we inherit. But at the very least, we are affected, often tremendously, by the sins of everyone around us.

If you grow up in an alcoholic family, the patterns and unhealth of that family imprints on you powerfully as a child. You’re affected and shaped by others’ sin.

Let’s say you never ad the brokenness of that alcoholism. Odds are overwhelming that you’ll start sinning in the mold you were raised in. Of course, you bear the responsibility for this sin. But it’s not only your sin. It’s an inheritance of brokenness.

These inherited patterns, attitudes, and sicknesses are powerful. They don’t go away with wishful thinking. At some point, the sin modeled to us becomes our own, and we start busily passing it down to our kids.

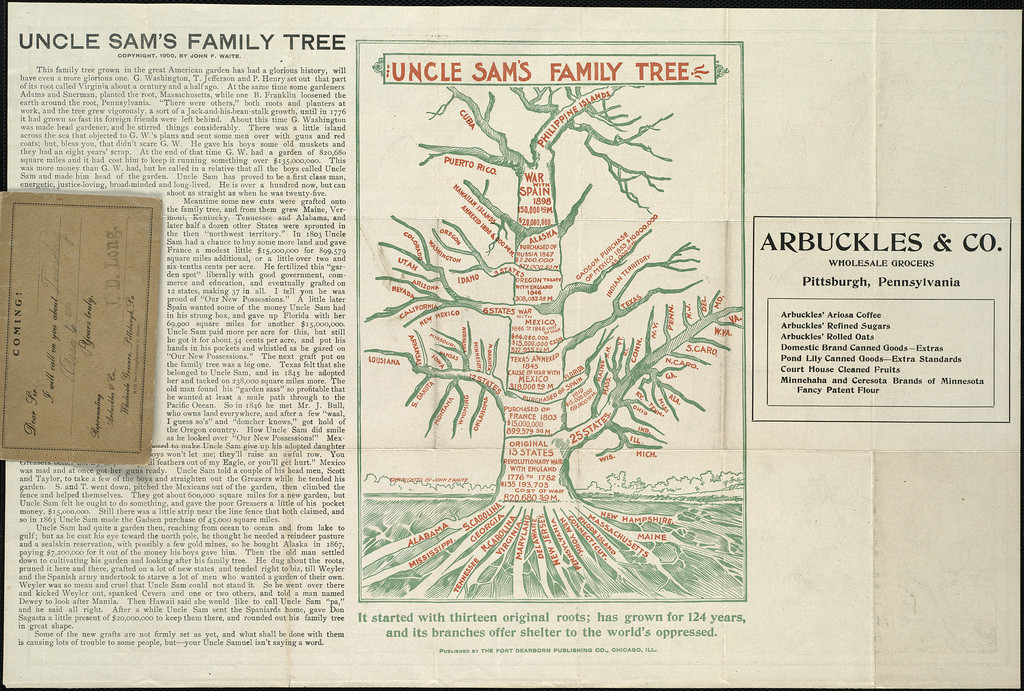

This is true in families. And it’s also true in societies. The more I learn about the hundreds of years of slavery and violence against Native Americans, African-Americans, and other people of color, the more I shiver. These patterns don’t go away with white people listening to “I Have a Dream” once every February. Unless we’re specifically, intentionally repenting of racism and all its repercussions, it still exercises its poisonous power over us.

Look: this is a pretty Biblical idea. Ham looks at his father Noah’s nakedness, and his descendants are consigned to be “the lowest of slaves.” Reuben sins against his father—all of his offspring get passed over in favor of Judah’s. Agag the Amalekite’s sin was so grievous that many generations later, his descendent, Haman, is still the arch-enemy of the Jewish people.

I’m not saying all sin is treated this way in the Bible—but both sin and blessing are often seen as collective inheritances. We must look critically at the systems and inheritances that affect us.

Next week: What we can do, practically, to ad the sins of our fathers, and why it’s so important we do so with alacrity.

For part two of this post, go here. For all the posts in the “beliefs I wish weren’t true” series, go here.

Image credit: Norman B. Leventhal Map Center

Sisterhood is a Practice: For SheLoves

Sisterhood is a Practice: For SheLoves

I wish this weren’t true either, Heather, but it’s hard to deny. You did a good job of making the distinction that depression, anxiety, and other mental disorders are not sin. But not treated, not dealt with, we risk more harm. I feel the weight of of family lineage, some days I feel it too much. Looking forward to the next parts of this series. Thank you for writing brave.

Thank you, Debby 🙂 I’m glad you think I did a good job on that distinction b/c people with mental health issues get WAY more crap than they need from the church. In many cases, I think the humility that mental illness gives us (realizing, for instance, that you can’t always trust the information your brain is giving you) actually leads to softer hearts, more eager repentance, and hard-won wisdom. I wish more of us took our own “realities” a little less seriously and saw that very often they’re biases, naivety, or even sinful attitudes. xoxox

Thank you Heather- so important to see the verse worked through seriously. Good news of course that in the Ten commandments when this theme of God’s visiting the children unto the third generation it is compared to his mercies visited to the thousandth. But am glad you didn’t use that to gloss over the real consequences. I know for myself reading your blog added greater depth to how I can see this theme worked out. Thank you so much.

Oooh, I hadn’t noticed the wider context of blessings vs. sins. Yes, in God’s economy, our sin is simply drowned in His abundant grace and mercy. It’s why we must desperately seek it, because just the smallest movement towards God sets off an incredible flood of mercy.