Dear Awkward,

What do you think if the Instagram account @preachersnsneakers? How do you see wealth, spending, and responsibility in church and or in the kingdom? Is there a place for judgement?

Mara

Dear Mara,

After I received your question, I decided to re-take the Slavery Footprint survey, and discovered that I, personally, employ 52 slaves. That’s a distressing way to begin an already grey Tuesday.

Slaves most likely mined the diamond in my wedding ring, the coltan in my smartphone’s capacitors, and the cotton in my shirt. I have never met the men, women, and children who work for me, but they work nonetheless.

Of course, I don’t know the exact number. I try to buy ethically made fashion, buy used whenever possible, and buy as little as I can, but I still participate in a global economy that brutalizes and enslaves people. That isn’t arguable.

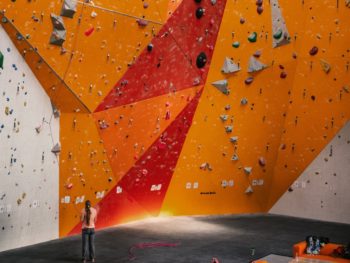

Look, I raise eyebrows at clergy sporting expensive clothes (though like the New York Times pointed out it has a really, really long history). I am glad I’m part of a church with regular congregational meetings to disclose pastor’s salaries and yearly financial disclosures that document how my church spends my tithes. We should be asking really hard questions about any preacher who manipulates others to support opulent lifestyles. Financial malfeasance in the church is a serious form of abuse.

So yes, five-thousand dollar sneakers on a preacher should probably provoke some hard conversations with elders and church boards. I’m fine with holding our clergy accountable for financial discernment.

But judgement from someone not a part of those congregations? I shift uncomfortably, remembering my 52 slaves. I’m not sure I’m in any position to cast the first stone. If a pastor makes a reasonable, ethical salary, and is transparent about their finances and values, who am I to judge?

Full disclosure: when I heard about @preachersnsneakers, I groaned, then gleefully wagged my finger at the pastors on display. Their conspicuous consumption made me angry. Then I read an article in the New York Times that tempered my righteousness.

I remembered that pastors are often held up to unfair scrutiny. They should look successful and yet be perfectly humble, and entertain like their congregants and yet live like monks, impress others yet never struggle with pride. Knowing the toll this takes on pastors’ families, I became wary of my knee-jerk condemnation.

It’s not that I think this kind of spending is great. It’s that all of us wade in a consumerist sludge, and we all stink. I know friends who have made radical choices to disconnect from the evil built into our economy and they still struggle with making moral choices. And for the rest of us judging these pastors while congratulating ourselves on our cheap Target kicks, we may be ignoring the terrible hidden costs of our frugality.

What I wish is that our churches made plainer how Christ’s words about rich men and camels implicate all of us. How our mindless spending (whether costly or cheap) impoverishes our souls. How our fast-fashion enslaves people bearing God’s image. How our quest for convenience degrades creation. And most importantly, I wish our churches modeled and taught practical steps to wean ourselves from the brutality of consumption.

Maybe we don’t because all of us, pastors and congregants (me included) don’t want to think too hard about squeezing through the eye of a needle. So instead, we pretend that if we’re not called out on IG, everything is fine.

It’s easy to judge or feel bad about ourselves. But Jesus calls us to real change. For me, that looks like seeking simplicity in my buying habits, trying to avoid buying cheap stuff for fun, researching brands and ethics, and making do with what I have. But I don’t do any of this perfectly.

No matter what I do, though, I can’t pretend to be standing on any kind of moral high ground. My slaves cry out like the Israelites of old, begging God to save them.

Three Reasons You Put Off Spiritual Disciplines

Three Reasons You Put Off Spiritual Disciplines