If I knew anything for certain when I was a child, it was that I was not the artist of the family—my older sister Katie was.

Looking at her work, I knew I’d never be as good as her. I wouldn’t even be in the same universe as her. Anyway, I had my own ‘talents’: school, and the performing arts, and generally being the favorite child. I didn’t need to do art.

That was her thing.

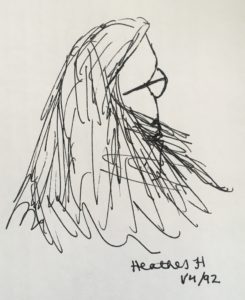

I felt nervous when I learned that for my ceramics class in high school, we had to keep a sketchbook. To my great surprise, I liked drawing.

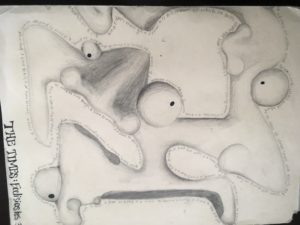

I liked that with nothing but pencils, pens and my own imagination, I could transform a blank notebook into something indelibly, creatively, mine.

I took a few more art classes in high school, and then one more in college. In those classes, making art felt like caring for a mean-spirited cat. Sometimes, it would curl in my lap and keep me company, and sometimes it would turn around and try to claw my eyes out.

Once, I used some new watercolor pencils to craft swirls of color on a page, thrilled with the freedom of abstraction. When I showed my tender risk-taking to my high school art teacher, he told me I should look at another student’s abstractions, because they were much better. I felt like he’d sucker-punched me.

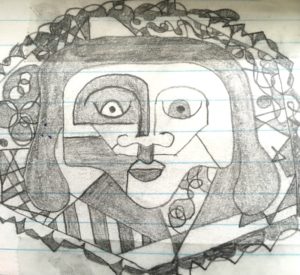

Later that year, I started making faux album covers for a made-up band I called The Cheshire Cats. At first I felt proud of my work, but later I felt dumb that I was playing around with words and fonts when my classmates were making real art.

And in a college drawing class, we were supposed to do gesture drawings of a bell pepper. When I glanced over at another student’s work, I saw a pepper. When I looked down at mine, I saw weird squiggles. My eyes filling with tears, I took my HB pencil and made a long gash down the middle of my newsprint.

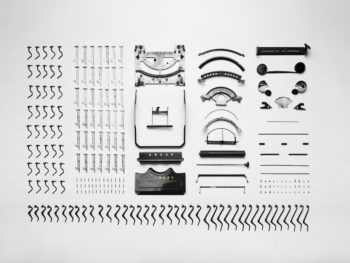

All this to say: most of my formal art training served to make me feel terrible about myself, my work, my skill. It mostly taught me to compare what I did to all the other people around me.

It kept me from making things.

The other day, one of my friends saw my sketchbook and said you’re such a good artist. She also said that she was not.

I wanted to take her face in my hands and tell her that all these words we use to judge our art—good, real, artist—they are MADE UP WORDS. They do not mean what we think they mean. They do not say anything useful.

I started making art more when my children were little. By then, I had been writing for a long time, and I’d learned that “talent” was a shell game. I bought my kids nice art supplies, and when they made things, I did too. I realized if “writers” are people who write, then “artists” are people who make art. I didn’t need permission to claim those names.

Making art still feels tender to me. Unlike with writing, which has felt mine for nearly twenty years, art feels a bit like using my left hand to cut a piece of paper. It’s awkward. I feel my lack of practice, especially when I draw.

I don’t care. Art making is not about skill, but about desire. The only question I want to ask about art is: do I want to make some? Do I have a picture in my mind I want to make real? Do I want to take a piece of discarded paper, or a recycled cereal box, and resurrect it into something beautiful?

Many of us hold back from making things because we feel incompetent and think lack of skill is a problem. It makes me tremendously sad to think of all the delight that attitude steals from us. It makes me angry to think of how we teach art, pitting one person’s joy against another.

Still: there’s a simple question for each of us to ask. Do we want to make something?

If the answer is yes, it is brave and bold and beautiful to set aside our fear and try.

Originally posted at Leslie Verner’s site.

Thinking of the Next Big Thing: For SheLoves

Thinking of the Next Big Thing: For SheLoves