Years ago when my kids were in elementary school, our small homeschool charter did a fundraiser at a local pizzeria. I decided—my heart in my mouth—to attend with my husband and kids.

Not long before, I’d finished intensive therapy to work through deep childhood trauma. It undid, then remade my life.

During the once-a-week sessions, I mostly stopped going to social events. It felt like I was walking around without any skin, so social interactions just weren’t fun.

But I assumed that once I healed, I’d have skin again. Surely I’d be even more social than ever. I’d be the life of the party, free and easy.

Instead, the opposite happened. Social events now filled me with terrible dread. The pizza party was one of the first times I forced myself to go out, despite my misgivings.

At the party, another mom, who also worked at the school, sat down to chat with me. “I’m surprised you’re here,” she said. “I’m so glad you came.”

I smiled. I liked her a lot. She was so kind. “I just find these events hard, since I’m so socially awkward.”

She looked confused. “You’re not socially awkward,” she said. “I’ve never thought that.”

I felt a surge of gratitude. She was gregarious, and lovely, and just the kind of carefree I always wished I was. Her words lightened my dread…a little.

“Thank you,” I said. She soon excused herself to talk to other people, and I spent the rest of the evening feeling hypervigilant and near tears. But, I thought, at least no one could tell. That was good, right?

After that night, I kept thinking over her words.

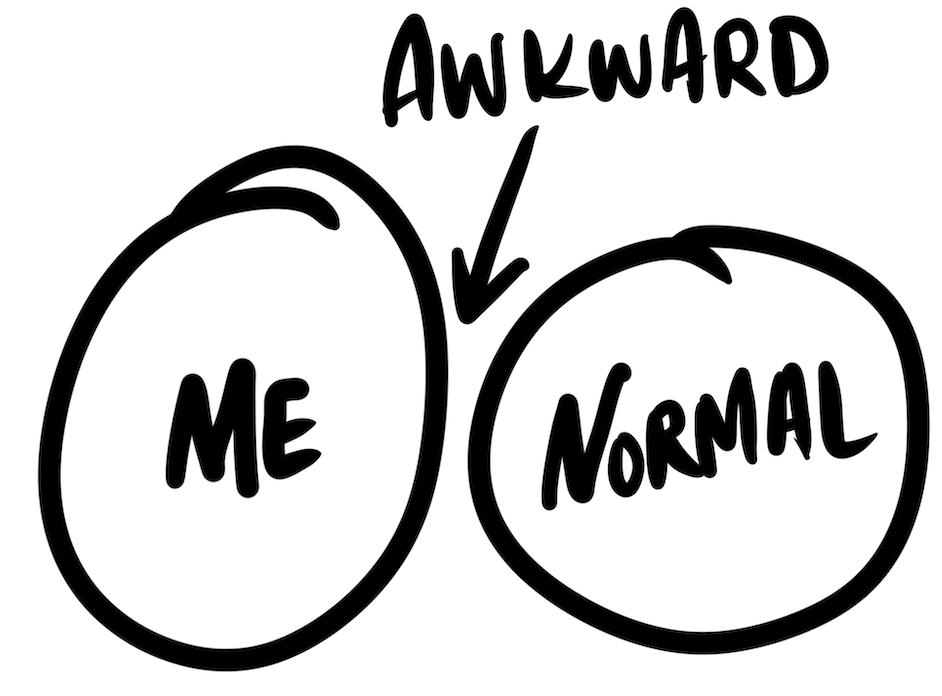

If I was not actually awkward, why did I always feel so out of place? Why did I feel like everyone around me enjoyed these community moments with ease, while I walked a tightrope, my heart in my throat?

Why would socializing feel like a high-wire act, as if I could slip at any moment?

And I did slip, sometimes—asked the wrong question, or looked around a crowded room of happy people and felt a vertigo that I had no idea how to approach them.

I often found myself in tears at these gatherings, or so uncomfortable it felt like I was on fire. The fact that no one noticed felt good, except for the fact that I also felt completely alone and unseen. It made me feel like a space alien.

If anything, therapy had made things worse. It was like I’d been wearing noise-cancelling headphones and therapy had destroyed them. The noise had always been there—but I could no longer ignore it.

All I wanted was to feel part of the group, but groups gave me hives.

All I wanted was to feel at ease, when instead I felt painfully awkward.

Now, nearly ten years later, I think I’m beginning to understand why.

After reading DL Mayfield’s God Is My Special Interest Substack, and consulting with a therapist who used to specialize in autism, I’m pretty sure I’m on the spectrum.

Suddenly, the awkwardness I’ve always felt—in social situations, in faith communities, and just in my own head—makes a lot more sense.

Like the idea of “normal,” I thought I understood what neurodivergence was until I actually started getting curious about it. Both my siblings have been labeled neurodivergent in the past (my brother with autism, which I’m unsure he has, and my sister with ADHD, which she definitely does have, and bipolar disorder, which she definitely doesn’t). Honestly, these labels often did them more harm than good.

Because of my siblings’ pain, I’ve long thought that instead of shaming, pathologizing and belittling people whose brains work differently, we should try to get curious about what they’re experiencing and then accommodate their particular needs. I have tried, especially reading disabled activists and thinkers, to stop prizing “normalcy” and start looking at the gifts and strengths of the impaired.

But that’s easier to do when it doesn’t affect me personally. It’s harder to be blithe about the strengths of disability when your difference makes you feel like an alien. It’s easy to say you aren’t ableist when you feel strong, or at least confident that you appear strong.

Admitting that I am awkward, at least on the inside, feels like a giant relief and also a giant vulnerability. I wonder if people will take me less seriously or prejudge me as a freak. It feels like going forward, no one will say, “you’re not awkward” when I want to be reassured I’m fine.

But I am awkward, even if I hide it well. People not noticing my discomfort and not having the discomfort in the first place are not the same thing.

I’m starting to wonder whether feigning ease is really worth the cost. It allows me to fly under the radar, but quite literally makes me invisible.

I have called myself an awkward Christian for years without really understanding why I felt drawn to the word. Like many autistic people, I’m candid to a fault. I say the hard thing because dissembling or pretending makes me feel terrible.

I have never been, nor ever will be—easy in social situations. I’m prickly, and can’t manage small talk, and feel everything too intensely for that.

There is grief in realizing my limits, but also power. Naming awkwardness is often a prophetic act. Now I understand why I feel fire to be honest about the abuse our society seems hell bent on ignoring. On my ability to name the insanity of assuming that labeling something “Christian” makes it healthy or kind. And even why autism, while it feels scary, makes me feel like I see myself clearly for the first time.

I’m just beginning my journey of unpacking what autism means for me. But I’m starting to understand why it felt like therapy made social situations harder: it got rid of all the ways I numbed myself to reality.

Reality is hard. But in the end, it’s where I want to live.

Name your own glorious difference with my creative personality test. Go here to take it.